We feed each other

Because who are we if we don't?

I live in a country that snatches food from the mouths of babies, whose social safety net (even in our best moments) is a single frayed thread. I live in a country that is somehow home to both nine hundred billionaires and tens of millions of people who don’t make enough money to eat. I live in a country where food banks (sacred places, neighborly places, but places which wouldn’t exist in a truly just society) were already seeing unprecedented demand for their services before this latest cursed moment. And, this week, I live in a country that is also a ticking time bomb, where we are all left to cross our fingers in hopes that tens of millions of SNAP recipients won’t be kicked even further to the curb.

I want to lament every single layer of it all— the private jets and the kids with empty bellies and the fact that Mike Johnson, an ostensible public servant, gets to smirk his way through television interviews without being asked the only question that matters. “Mr. Speaker, what did you get in return when you sold your soul?”

I want to talk about all that, to offer an outstretched hand to those of you white knuckling it through this week, as well as a plea to all those of you who are (currently) fortunate enough to not fear hunger. But I also have a story to tell, one that might seem hopelessly orthogonal to this moment but that I swear is connected.

I was in Minneapolis on Saturday. I had just dropped off a carload of Quaker middle schoolers at a retreat in Eau Claire, Wisconsin and, suddenly childless and with a few hours on my hand, I tried something new. A few days previously, I had reached out (via this newsletter) to friends and readers in the Twin Cities. I made a simple sign-up sheet, and invited people to hang out with me at Bichota Coffee on George Floyd Square. And people did. The absolute best people. You know who you are. Thank you for coming. Every conversation was insightful and hope-giving and connective. Highly recommended.

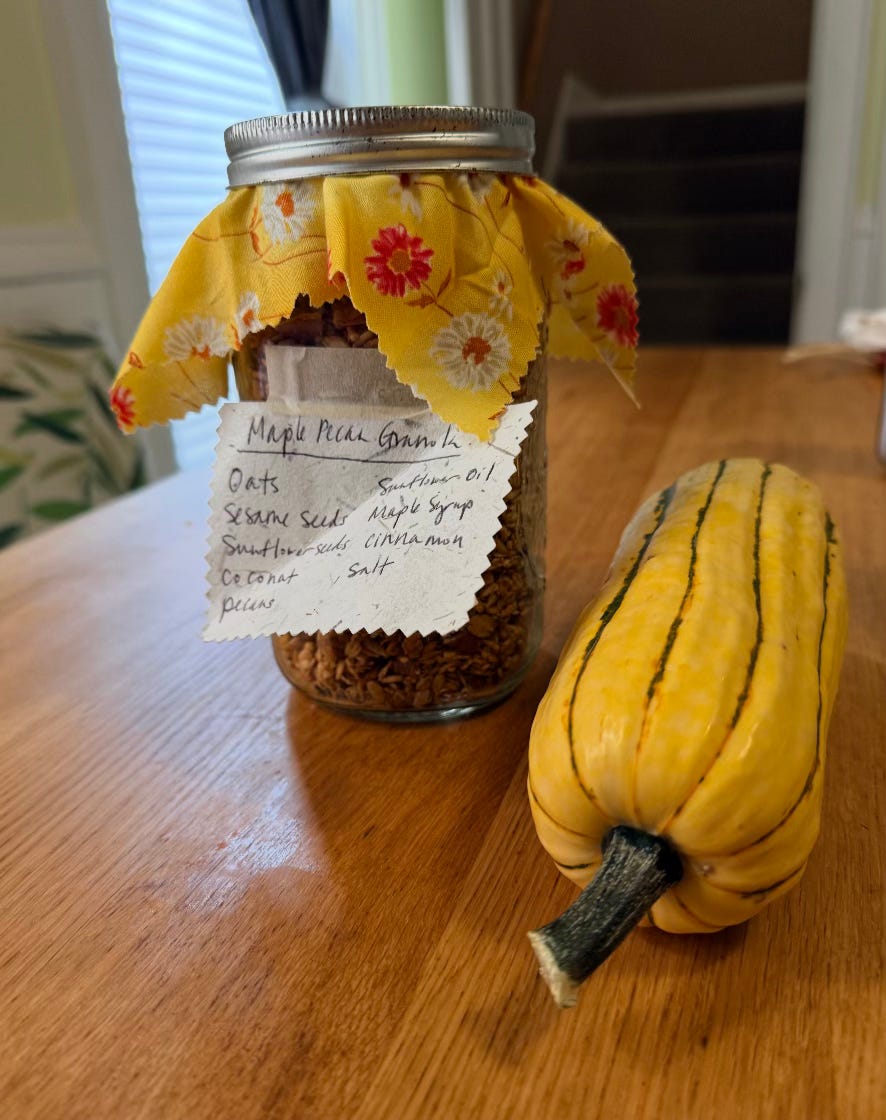

What I didn’t expect (perhaps naively, since if I am currently known for anything in this niche corner of newslettterdom, it’s that I can’t shut up about potlucks), was how much of that afternoon centered around the sharing of food and drink. Sometimes from me to others (I treated a couple people to coffee). Sometimes from others to me (you all, a reader showed up with a jar of granola and a delicata squash from her garden!). Sometimes from strangers to each other (at one point a woman, likely somebody without a home, fainted at the front of the store; I rushed to help her up and, by the time she was on her feet, she was welcomed by multiple outstretched hands bearing granola bars and bags of snack mix). And, by the end of the night, in my favorite form of all (an open table, this one laden with shawarma and cupcakes, in honor of an author’s book launch, but from which nobody was turned away).

In a world of great need, none of these offerings were, in and of themselves, enough. But they were perfect (which is to say, perfectly legible, perfectly familiar and offered by perfect hearts). From the lasagna dropped off at our parents’ doorstop the day we were born to the foil-topped dish of funeral potatoes our loved ones will share at our memorial service, we know it instinctively. When we are loved, we are offered food. When we love back, we offer it in return.

That night, after a day spent watching this absolute alchemic miracle (interconnection, made tangible in the form of granola and cupcakes), I checked into a hotel room. I was exhausted, so I absent-mindedly flicked on the TV before collapsing on the bed. The Bill Maher show was on. I had never actually seen it live before, so I thought why not. We all make mistakes.

Everybody on the program that night was an impressively resumed political figure of one variety or another (a former head of the RNC, a communications guru for the Biden administration). The “big” guest was Andy Beshear, the Governor of Kentucky. And listen, I knew going in that Bill Maher wasn’t my kind of political dude, but oh my goodness the whole affair was even more soul deadening than I could have predicted. The theme of the evening, far as I could tell, was self-congratulation. Maher and his guests said things like “I’m a lonely member of the wing of the Democratic Party that believes you should talk to the other side” and “unlike the left, I actually care about winning,” which is all fine and good, but they never explained what any of that meant in practical terms. It was all just rhetorical victory laps over an imagined set of Brooklyn haters. Maher interviewed Beshear, but the only questions he asked were (in essence) “are you going to run for President?” and “so, why haven’t you been meaner to trans people, it’s what the people want, you know?” Beshear, in response, offered answers that neither infuriated nor inspired. He was fine, I guess. The show wasn’t.

I turned off the TV after about fifteen minutes, so I don’t know how it all ended.

Maybe, after I fell asleep, Maher and his panelists eventually talked about forty two million people who rely on SNAP benefits to survive. Maybe they talked about the multiple places in the world (Gaza, South Sudan, Haiti, Mali) experiencing active, preventable, human-caused famines. Maybe, midway through the taping, they couldn’t take it any more— the cognitive dissonance between all that vapidity and fluff and the actual state of the world. Maybe they tore off their mics and walked out of the studio until they ran into somebody standing on the street holding a cardboard sign. Maybe they said “you hungry? Me too, let’s share a meal.” Maybe, realizing the size and power of their platforms (and eager to atone for lives wasted on self promotion), they’ve since started a hunger strike in front of the Department of Agriculture.

If any of that happened, I didn’t hear about it.

Instead, I woke up the next morning, got in the car, and headed towards Eau Claire. I drove past dairy farms and ag schools, reminders that there is more than enough food to go around. I picked up the middle schoolers and treated them to lunch at a jam-packed Culvers in Mauston, Wisconsin. We sat next to a church group, a big crowd of college-aged kids who all ordered that restaurant’s generously-sized kids' meals (true Upper Midwesterners know). I took a picture of myself using a filter that made my head look like a cheese curd. It was silly and stupid but the middle schoolers chuckled politely. Over at the next table, the church group argued over whether they preferred Perkins or Dennys. They and we were happy and full and together.

I could use a whole lot of words to describe my politics, but the most honest answer is that I believe in a world where everybody is fed, without exception. Also a world where everybody is clothed and housed and educated and treated with dignity when they’re sick, but there’s a particular primacy to that first one. At a bare minimum, let’s stop starving each other and pretending there’s nothing we can do about it. That’s socialism, yes, but that description alone feels insufficient. I care about the destination, but also how we get there. Yes, tax the rich. Of course! And also, we enabled this world when we first started worshipping a God called money rather than trusting the people around us.

My dream isn’t just for a world where nobody goes hungry, but one that we build by feeding each other. I want a world where we pay attention to the state of our hearts as food disappears and appears, where we don’t ignore the ache when we find that another human being is starving, and where we remember the way our hearts swell when we ourselves are fed. I believe in a politics of tables overflowing, both as a result of benevolent public policy but also because we, the dreamers, have plenty of practice actually filling physical tables with food.

I grew up in the era of “starving children in Africa,” so I know that talk about hunger and starvation can quickly veer into paternalism and pity. I’ve heard the phrase “people less fortunate than us” hundreds of times, a dichotomy that, while well-meaning, needs to be thrown in the ocean and never heard from again. There are not people who feed and people who are fed. There is just all of us, hungering for each other, stuck in a world— the one with the billionaires and the famished side by side— that has starved all of us of what we crave the most.

I don’t think any of this would impress those Beltway power players on the cable talk shows. Their world isn’t ours, though. They can keep their polling data and quippy rejoinders. They would say something about how their approach wins elections, whereas mine is romantic but empty and somehow the reason that Trump won. My response? I understand the fear, but those “adult in the room” bloviators have been steering the political ship for decades now and where has it gotten us? Right here, stuck in this cruel, triangulated present, where millions of people are about to lose the only lifeline that allows them to eat. So my God, forgive me for not being impressed that back in 2018 the candidate they consulted for outperformed midterm expectations in a suburban Virginia district. Can they please just lay down in front of Congress or host a fundraiser or serve some chili in the park for a change.

I may be wrong. Politics may, in fact, be the domain solely of the talk show yappers. But forgive me for craving something more satisfying than another joyless slog towards some pragmatic but hollow McKinsey presentation. If I dream of a world where everybody is fed, then that means I too dream of a politics of feeding each other now. Not as charity. But because when you were loved for the first time, there was food. And when you are loved for the last time, there will be food. And so if our movement loves, we have no choice but to do the same. In the politics of my dreams, you will be fed, and you will be asked to feed others. The food might not always be delicious and we might not always know how to connect with each other and sometimes I’ll tell the same dumb jokes as I ask you to pass the ranch dressing, but we won’t give up. We’ll feed each other, over and over again, until we can no longer even remember a world where any of us went without.

End notes:

Readers in the U.S.: In the spirit of feeding each other, please step up for your local food bank this week. Like I said above, we deserve a country where we don’t need food banks anymore, but we’re not there yet. So please, give money if you’re able, volunteer if you’re able (so many people I love have had their lives and politics transform for the better thanks to a regular volunteer shift at a food pantry) and, just in general, look for opportunities to feed one another right now. And, in the spirit of interconnection, please take me up on this offer: I will match up to $500 in White Pages reader food bank donations this week. After you donate, just fill out this form (I’ll trust you, no need to send a receipt). You’ll notice that you can share what food bank you donated to, and also specify whether you’d like me to have my match go to your food bank or if you’re ok with me sending it to the Kinship Community Food Center here in Milwaukee.

Shout out to Anne Helen Petersen, who is doing a similar match with her readers.

If you need help right now, here’s an interactive map to find food pantries near you.

Also, calls: Make them! Light up those switchboards.

I realize this is late notice, but if you’re in Milwaukee, TONIGHT at 7:00, I will be speaking to the Kairos Community (yes, a Christian space, but not the kind of Christian space you wouldn’t enjoy if you aren’t a Christian, I promise) as part of their “Living Faith” series. My sense is, I’ll answer a lot of questions about my life and the big questions that define it. It’ll be at Grace Presbyterian at 2931 S Kinnickinnic.

Slightly better advance notice (and open to everybody, wherever you live, because it’s virtual): on Tuesday, Nov 4th at 1:00 PM Central Time, I’ll be doing a Substack Live with Lisa Sibbett of the truly excellent The Auntie Bulletin

on public and private schools (ooh, an emotional topic which we’ll discuss with conviction but also love!)

I was debating whether to mention this week that I have a few more POTLUCKS! hats available, but given the topic, it feels very appropriate (and you better believe that I wore mine all weekend). If you’d like one, they’re not for sale; they’re a thank you for paid subscribers (because no, my newsletter is not the most urgent cause to support right now but it is my literal day job so I am deeply appreciative of all the people who sustain this work). If you’d like one, after you upgrade to a paid subscription, just toes me an email (garrett at barnraisersproject.org) with your address and something to the effect of “one hat, please!” and I’ll get it out to you.

Ok, ok ok— here’s the picture of me with a cheese curd filter. You’re welcome, Culvers. I don’t understand your current “curdtoberfest” promotion, but I took the bait because it made a couple middle schoolers happy (or at least willing to play along for the sake of my adult ego). Guten curd, indeed.

18 months ago the social justice action committee at my congregation was looking for another project. Believing that nothing would happen, I suggested we adopt a school and participate in the National Backpack program (bagging enough food for a child on the "Free School Breakfast and Lunch " program to carry on the school bus for the weekend (I personally knew families where weekend fare was powdered Kool-Aid.) We chose an elementary school I'd worked in years ago, learned enough tech to set up weekly volunteer jobs to maintain the program for a semester and explained it to members of the congregation, requesting that those who could do so either volunteer or donate. Our goal year 1 was 20 bags (= 20 students) and a commitment to weekly shopping, packing and delivering to the school. Funding started pouring in. Volunteers started committing. In this congregation of 120 families we ended up with 33 volunteers and 123 contributors. By our December eval, it was clear that the congregation had embraced the program. Families who were themselves just making it found ways to contribute.

Grateful as I was for the surprising response, I was and still am losing sleep over the knowledge that there are 150 children of the 600+ in that school who need the food to get through the weekend. There are families where one child gets a bag each week and the siblings don't.

The congregation kept working at it and this year we are doing 30 bags a week--that's 20% of the need. We've started receiving significant contributions from friends and relatives of congregants who are as far away as Texas, all helping us get to the 30 bags a week.

Sunday young families brought children aged 4-17 to pack 3 weeks worth of bags as part of a community outreach day. Before leaving they asked if they could come back again to help. The program matters, but also smacks of patriarchy despite our having no idea who the specific children receiving the bags are. And yet my nightmares continue.

What about the other 120 hungry kids? Why should we need this program at all? What happens if the Board of our congregation decides not to allow us to continue because the donations are needed elsewhere? What if the programs that feed these kids gets demolished? While I don't want the Canadian version of socialism, we need better answers, and we have needed them for well over 150 years.

As usual, this gives all the feels. I've basically stopped listening to "political figures" that very clearly have never engaged in anything grassroots or community or neighborhood related. If a person has never borrowed a cake form and returned it with a slice of cake, or has never awkwardly attended a community gathering where nothing was left but pure humble humanity, I don't want to learn anything from them.

(Clearly always here learning 💜)