Subverting the Game: It's all made up, let's make up something kinder.

A guest essay by Sara Sadek

Top note (from Garrett): Hi friends. Thanks for being here. Today, as a special bonus, I wanted to share an essay by a writer and human being who I’ve long admired. I’ve known Sara Sadek for just shy of a couple decades now (jeez!), through moves, changes in jobs, relationships, worldviews, etc. Through it all, she’s consistently been one of the wisest and thoughtful people I’ve known, and I love that the world now gets to read her writing.

This piece in particular is a great introduction to what I love about Sara. It’s a personal essay, yes, but also part book report/part meditation for this moment when so many of us are trying to reckon with identity, biography, and matching our actions to our values. It’s stayed with me since it first hit my inbox.

Here are a few ways to support Sara’s work:

If Sara’s writing speaks to you, you can subscribe to read more at Folkweaver. It’s one of my favorite reads.

Sara is also kicking off an upcoming Folkweaver workshop: Release to Reimagine Oct 28 (paid subscribers get 20% off plus access to writing circles and 4th Friday book club whose current book is Imagination)

Finally, Sara is a coach who “holds space for folks doing their work 1:1, whether it be around creative practice, family life, or imagining into being different ways to create the world we dream here and now.”

I woke up at midnight and wrote the letter, then tucked it into the book on my desk.

The rest of the night I didn’t sleep. In the morning, I loaded the kids into the car for Tahoe and drove, my mind racing faster than my car. When we got there, I agonized into the evening before finally building up the courage to text him, “There’s a letter for you tucked in the Book Saving Time on my desk.” That book because I hoped the letter would finally save us both from wasting any more of our time.

Several minutes went by before I got a text back. “I read your letter. I agree. How do you imagine we do this?”

There’s this game we’re all playing. A small group of humans made it up. This is the game: to crush or be crushed. Nearly all play it without consent.

Most play it from below, getting crushed. A small minority play it from Above, doing the crushing. The ones Above are enforcing the rules of the game. Those rules help them stay Above. The rules are White Supremacy, Capitalism and Patriarchy.

We had been a couple for two decades, married for 14 years, and parents for nearly 10. But ultimately, we couldn’t agree on how to play the game.

The game is absurd and dangerous and most humans don’t like playing it. Near its end—if played by the rules—the game looks like this: most of the humans from Below scrambling either to get to the Above, or just to survive in the Below: clawing to get out of holes within holes, only to find themselves in bigger holes not of their own making.

He is a cis-het white man from a suburb of Minnesota. A black sheep democrat in a sea of republican family. I am a neuorqueer Egyptian-American immigrant who grew up in Madison, Wisconsin. Maybe it should have been clearer, sooner, that we’d be wired to play the game differently. But beneath serving as pawns with different roles on the board, we are complex humans and it’s never that simple.

To be Below is to be crushed by the Above. Most of us are playing from Below, working in the direction the arrows point, trying to escape being crushed by becoming a part of the Above: part of the ones doing the crushing. If we refuse, we stay Below, getting crushed.

In her book Palestine 1492, Linda Quiquivix explains the game like this “When all one knows is that those above live in some kind of stability, control, and even fun while crushing you down below, desiring to be just like Them can be an overwhelming temptation.”

He is a serial entrepreneur with a penchant for big dreams and bigger risks in the hopes that playing would one day break the game, at least for our family, making us one of the Above.

I am a neuroqueer immigrant who abhors the game. I played it for survival as a kid—assimilating into whiteness and losing my identity in the process—but over time, I intuitively learned that no matter how much I assimilated, it was not designed to serve me. In adulthood, I’ve spent my life’s work grappling with how to break it, bend it, manipulate it, exist in spaces outside of it.

While he worked in tech at breaking capitalism and becoming of the Above, I worked outside the game to create countercultural community for me and our babies—microcosms of the world I want to live in—organizing connection parenting playgroups, mother’s circles, forest preschool cooperatives. The unpaid labor of care.

Some people play the game differently, whether by choice or circumstance. Quiquivix describes how some sociologists warned of this trend, which they’ve coined “downward assimilation”:

For children of today’s immigrants, sociologists have coined a term, downward assimilation, as a term of caution. It’s what they call Brown people who share their lives and fates with Black people more than they do with White people.

‘That’s me,’ I thought when I read it, relief washing over me. An immigrant. A Downward Assimilator. A rejector of the striving to become of the Above. How clarifying.

To sociologists wishing to preserve the game, downward assimilation might be a warning—look at those humans not playing the game right. But in my body, “downward assimilation” feels a lot like the winding journey of building an antiracist + decolonized + anticapitalist + intersectional feminist + neuroinclusive + working class + disability-justice + LGBTQIA2S-justice lens. A lens for the rest of us. In other words: a lens of liberation.

I did all of my post-motherhood as a Downward Assimilator, organizing communities of care as unpaid work, because 1) that is the work of building the world I know is possible, 2) capitalism doesn’t compensate care work 3) his striving made me financially able to opt out of trying to monetize my care—at least for a while.

Until that time we lost our second baby, and shortly after that he lost his job. Then we were both free-falling into the below, scrambling for any ledge to grab onto.

Trying to opt out of the game feels like punishment, and that punishment is severe. Punishment looks like not having a job that covers healthcare or pays for rent or buys groceries. Nearly all humans playing the game are scrambling, most of us too inundated to see the billions of other humans from Below scrambling ever more frantically right next to us to survive this game not of our own making, not designed for our thriving.

We were free falling partly because capitalism is ruthless, and partly because I was a Downward Assimilator, opting to raise our babies and build community, leaving us precariously single-threaded in the game of striving for the Above.

Near the end of the game, while the Above starts to buckle under its own weight with gluttony and greed, the Below dodge its crumbling infrastructure, yet still have to survive within it somehow—working to land that job that never comes or pay the bills that stack up higher or buy groceries that cost x times what they used to.

At his plea during our freefall, I yanked myself out of the microcosms of a world of care I’d built alongside community—an antidote to the game—to become an unwilling pawn again. It was painful, but we needed to stop our financial freefall. I masked up, put my game face on, and started up my DEIB consultancy, advising white leaders on incremental change, making my 3D world 2d again, trying to infuse some of the lessons I’d learned from my time opting out into the game whenever possible, teetering once again on an evaporating middle-class tight rope in a city with no tolerance for the in-between.

The game is rigged. Above or below. To crush or be crushed. These are two heinous choices.

I played well—doing the emotional labor to hold white folks through their work. My business grew. We found stability. I had a four year old, a consulting firm, some semblance of safety.

Then—seven months into my next pregnancy—COVID hit. Suddenly, I found myself home with two children under five—one an infant—at home, a job, wildfires, and no childcare in sight. I kept it all in the air for a while until, like so many mothers during COVID, I just could not any more. I opted back out and wound down my consulting practice, a mix of relief and defeat. We made do for a while— until he lost his next job and we find ourselves free-falling again, repeating the cycle.

He sends me tech jobs in AI to apply to, thinking I will have the interest, the access, the energy to play again. This time, I finally understand what’s happening: he loves Star Wars, but wants me to work for the Empire. He wants me to play the game his way—striving for the Above to keep our family safe. But I can’t play the game that way. I don’t want to be crushed, and I refuse to do the crushing. I need a third option.

Whenever I face a binary of two bad choices, I look for a way to create a third path. Like so many of us, I am done with this game. I want to gather and write and think and read and organize with people looking for ways to subvert it, to break it, to withdraw from it, to cut off its oxygen source. I want to change the conditions of the game—together—so that it becomes obsolete.

Learning about downward assimilation got me thinking: if immigrants can find different ways to relate within the game by connecting to black and brown folks and distancing themselves from the Above, is connection the primary way to go rogue? This game only survives off our disconnection. Can connection subvert the game?

Quiquivix says:

“People seem to believe the chess board is the only nature of the world, the only possible configuration of the world. “

What if that’s not true? If the game is all made up, and the conditions of the game are asinine, why can’t we change them? In Che Guevara’s Guerilla Warfare, he says,

It is not necessary to wait until all conditions for making revolution exist. The insurrection can create them.

Insurrection is an intense word, but what if instead we said: we, the people, can create the conditions to change the game.

Quiquivix says:

They say the chessboard hasn’t changed for 500 years. If it’s true it’s not necessary to wait for the conditions to change…then what if the pawns changed the chessboard conditions? What if the least powerful, the anonymous front lines, the ones sent out first to fight and first to die, the disposable ones, the least valuable ones changed the conditions? What if the ones below could change the landscape of battle by changing their relationship to each other? (emphasis mine).

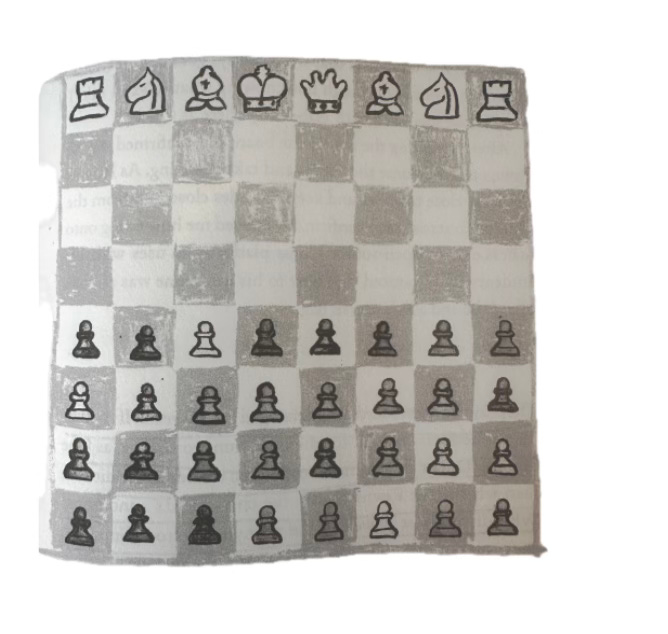

Here’s an example of an illustration she shared from a series called La Vida en el Ajedrez, Life in Chess. This illustration is called Revolución, and has 32 pawns against royalty and their guards.

She played this image out in real life and discovered this truth:

32 pawns on a chess board can overpower the pieces and capture the king, not by changing the power of the pawns, but by changing their relationship to the pieces. And by changing their relationship to each other. (emphasis mine). In order to shake off the oppressor, the Pawns must stay close together, keeping each other safe while moving forward, knowing some will be martyred. Still, while the odds of winning are good, winning is not a guarantee.

I looked at his text, “how do you imagine we do this?” and gave a sad smile. He wasn’t willing to imagine me playing the game differently,, but at least he was willing to imagine how we might change our relationship—to finally give us the space to move more freely on the board, each in our own way. To free me up to keep building with those willing to change the game together: folks who know we can subvert it by deepening our relationships—not from above, not from below, but side by side, in this winding quest for liberation.

End notes:

From Sara : If this piece spoke to you, I write weekly and host learning circles over at Folkweaver about connection and creativity as our pathways to liberation. Come join me!

From Garrett: I really appreciate this community for so many reasons, but one of them is that you are open to this space highlighting other writers/voices. Thanks again, you all (and if you’re looking for my usual bevy of announcements, they’re at the bottom of my essay from yesterday).

Thank you Garrett for decades (!) of time watching one another evolve, and for giving this essay a share on the White Pages. Grateful for all of it.

Could not possibly have come at a better time. I've spent the past decade working with colleagues and collaborators to articulate what, exactly we can do to change the rules of the game that we play by self-governing (a) our own communal relationships and (b) our work as academics. I never meant to be an academic, spent most of my offer decidedly not one, and according to most prestige paradigm measures, I don't really count as one now. But I do teach and study as a contingent faculty member (words that didn't mean anything until about 7 years ago, and that any previous version of me would have never understood). While I definitely am working adjacent to the Above right now, I grew up deeply Below, most relate to that, and can basically only see the academy as a place of potential redistribution of access and resources. I find enormously helpful Sara's metaphor of The Game amd the reality that if we play it, we can rewrite The Rules. A lot of my paid work right now is developing training and support systems to help people reinvent the rules when they have spent their whole professional lives in the academy and don't reallyknow how to see the rules, let alone believe they can change them. Thanks for this very helpful framework, Sara! I'll definitely be sharing it.