Seven reasons why hosting a silly little potluck (or game night, or porch hang, or book club, or group hike) is essential to defeating fascism

Honestly, I don't think we'll win if you don't

Over the past few weeks, I’ve fielded the same question dozens of times, always well-meaning, always anxious. “You’re in contact with activists in Minneapolis. What should we do now in case we’re next, if ICE occupies our city the way it’s terrorized that place?” It’s a new variation on an older question, one which rears its head whenever the contradictions of a system built on violence and caste become harder to ignore.

My answer is predictable and, I fear, often disappointing. It doesn’t offer a hero’s path. At first blush it doesn’t match the urgency of the moment. That question (“what do I do?”), leaves so much unsaid (I’m frightened! I feel powerless! I want to take an action that will both calm my heart and send the gun thugs running!). We want to attend a training today and suddenly be leading a neighborhood rapid response group tomorrow. We long for an invite to the secret meeting where every perfect activist step is laid out before us like a treasure map. We crave, whether we admit it or not, “one simple trick,” that will reverse all the ways fascism makes us feel impossibly tiny.

I understand, friends, that not only am I a broken record, but that the song I keep playing sounds like some effervescent bubblegum pop trifle. I understand also that you’re likely hearing the same chorus played from an increasing number of speakers, and that perhaps you’ve grown tired of it by now.

But there’s a reasons why, at the protest I attended last Friday, no less than three speakers talked about community (to a crowd that was actively sharing hand warmers and sandwiches with one another, no less). There’s a reason why Adam Serwer of The Atlantic coined the term“neighborism,” for the variety of resistance that’s emerged in Minnesota, and why Jelani Cobb, Dean of the Columbia Journalism School, recently opined that “in a democracy, the fundamental civic unit is the neighbor.” There’s a reason why Amanda Litman, whose day job as the leader of Run For Something is pretty damned political, earnestly believes that hosting dinner for friends every Saturday was the “most political thing [she] did in 2025.” And there’s a reason why my favorite foil, Ezra Klein, is now talking about hosting, if not a potluck, then at least some variety of gathering.

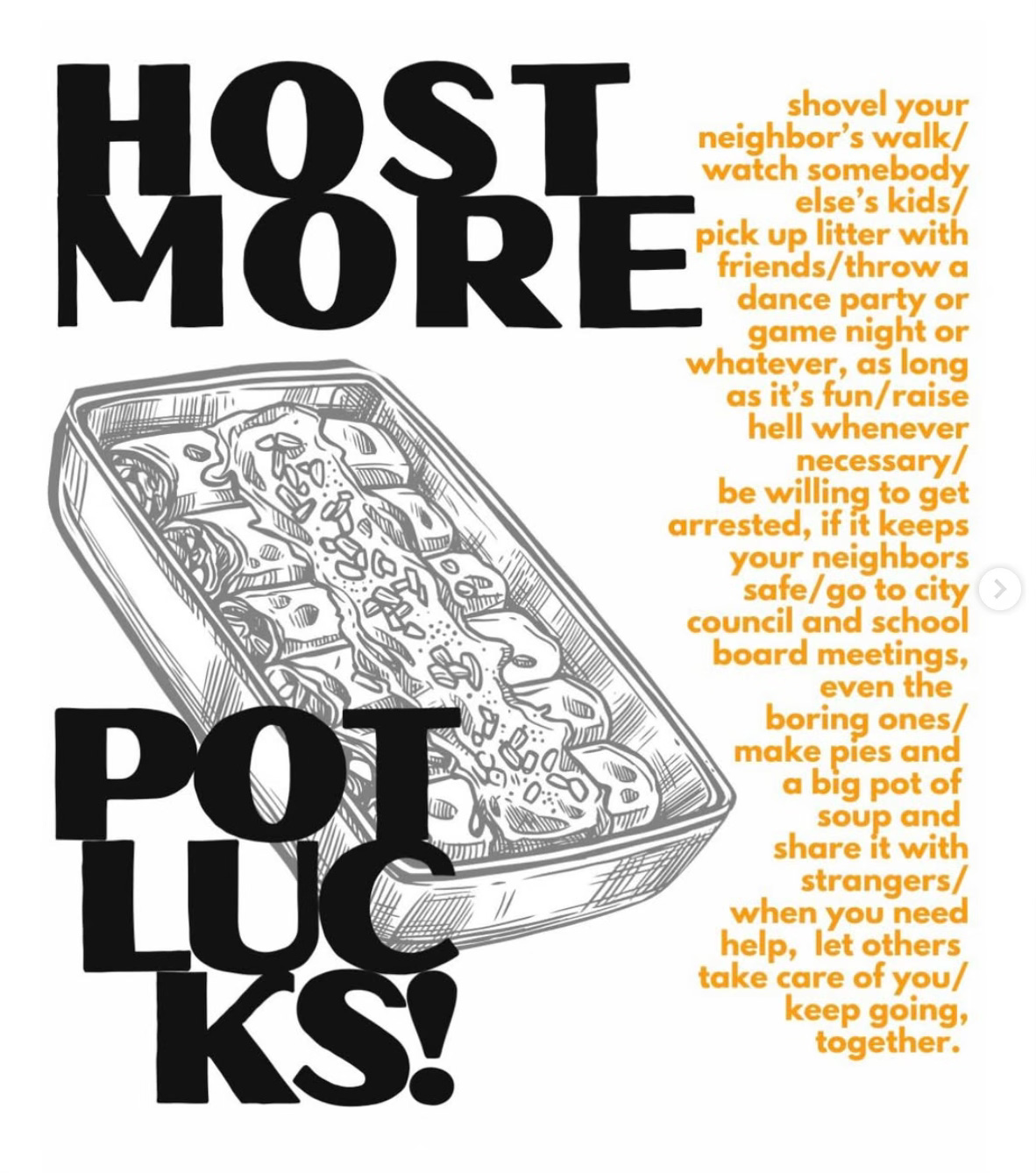

You are hearing the same chorus, not because it’s a hip trend, but because it’s true. My friends, you really do need to host a potluck. You need to bake cookies and write little notes inviting your neighbors to a block-wide Signal chat. You need to untether yourself from the urge to clean your house or whip up a fancy meal. You need to host stoop coffee and hang up flyers for park hangs and register for a potentially disappointing community rec class. You need to ask yourself “what’s the thing I most like to do with other people?” and then take the risk of inviting people, even strangers, to do it with you. These are not pleasant distractions from fascism, nor mere salves for loneliness. We need them. Urgently. They won’t feel like enough (and there’s not a guarantee they will be), but now is the time to build community like our lives depend on it.

Here are a few reasons, seven to be exact, why all this community talk isn’t just a cute distraction from the real work of liberation. The message here isn’t just that we’re stronger together (though we are), it’s that we ignore each other at our peril.

Build community, my friends, because our lives do, in fact, depend on it.

REASON ONE: The skills you and your neighbors need to resist fascism aren’t actually all that hard to learn. What’s going to slow you down is not knowing each other in the first place.

If you ask activists in Minneapolis how they’ve actually spent the past few weeks, you’ll hear about sets of actions that are either incredibly intuitive or that can be taught in relatively short workshops. There’s nothing particularly tricky about learning the SALUTE format for reporting ICE activity. You don’t need a doctorate in social movement theory to organize a food delivery spreadsheet. We all know, intuitively, how to blow a whistle. What is time consuming, however, is vetting strangers who want to join a Signal group, knowing which nonprofits can offer fiscal sponsorship for a mutual aid campaign, which churches or businesses have room for an emergency meeting, and who on your block is more flexible during the day or the night. The people who have been most effective in Minneapolis this past month aren’t the big talkers with the loudest megaphones. They are those who already knew their neighbors, who could be key connectors when, on a dime, an entire city raised their hands looking for something useful to do.

REASON TWO: Sure, you’ll eventually need to build relationships outside of your existing social spheres, but you won’t learn those skills if you don’t practice with those closest to you first

There’s a counterpoint that I receive pretty frequently, when I tell people to just host a damn potluck. Its a presumptive critique, resting on the cynical hypothesis that not only will prospective community builders only reach out to others who share their same class, racial and political background, but that they will inevitably stay stuck in those same bubbles forever.

I’m actually sympathetic to this concern, to a point. There are absolutely examples of ostensibly “community minded” efforts (particularly in white, professional class circles) that exist primarily to protect privilege and fortify echo chambers. America is dotted with wealthy neighborhoods that can throw a solid Memorial Day BBQ, but whose residents oppose every new affordable housing and school integration initiative. There are no shortage of ostensibly “welcoming” megachurches, but whose doors are only truly open to those able to walk a very specific path.

The problem with this rebuttal, though, is that it disregards how human beings build and strengthen new behavioral patterns. Having trained thousands of community builders across the country, I find that the neighbors who are most skilled at cross-community relationships are those who first exercised their muscles close to home. That’s the difference between being a colonist or a savior versus somebody who just can’t help expanding strong webs of connection outward. Instead of aimlessly tilting around trying to find somebody else’s community to welcome you in, you act as a representative of a loving network ready to meet similarly bonded groups on equal terms.

There are beautiful examples of this approach in Minneapolis right now. I’m being deliberately vague, to protect activist identities in a high pressure moment, but some of the most trusted organizers across that segregated city are skilled bridge builders who simultaneously do an incredible job of convening welcoming events in wealthier, whiter, more sheltered corners of town, but who also build trusting coalitions with fellow organizers from Black, Brown and working class neighborhoods.

Another example. Here in Milwaukee, a good friend of mine (who also happens to be one of the most skilled community organizers I’ve ever met) recently founded an alternative church, the Kairos Collective, based on an ethos of radical hospitality. The group that coalesced around him, at least initially, shared a lot in common. They were disproportionally white, middle class, and straight Gen X parents. But they intentionally practiced taking care of one another, and then slowly and patiently forged new ties with like-minded communities across the metro area: a majority Black congregation with deep roots in its neighborhood; a younger congregation with a large percentage of queer and trans members; a participatory food bank whose clients are also volunteers. The Kairos crew has been able to forge strong cross-identity relationships, not in spite of their focus on building trust with each other, but because they practiced how to care before reaching out an open hand.

There’s a key difference between the gated “communities” that stay closed forever and the connectors whose webs keep pushing outward. Shared spaces stay insular if their goal is to reinforce traditional power structures. If, by contrast, they exist to challenge power, they can’t help but seek out new ways to blossom. That’s the difference between something dying and something being born.

REASON THREE: Bodies in motion stay in motion, bodies at rest stay at rest

Relatedly, if “politics” is primarily a passive act where you consume content and react to people who rely, for their careers, on making you angrier and more helpless, you aren’t actually building new muscles. If the only action you’re ever asked to take is to call Congress or occasionally pound out a strident social media post, your political imagination will be perennially stuck in the borders of our suffocating present. “Politics” will remain distant and unknowable, practiced by a set of characters whom you correctly suspect don’t give a damn about you or your loved ones.

In contrast, here’s what happens when you commit to meeting more of your neighbors. You are introduced to their networks. You hear about a broader set of actions taking place in your area. You get invited to meetings, protests, and parties. Doors will open, none of them promising the immediate death of fascism, but all of which are useful, connective and that keep you moving.

To be honest, I still have a long way to go in meeting all of my neighbors. I’ve reached out to everybody on my block, but we still don’t all know each other. There are still parents at pick up with whom I haven’t had a real conversation. There are still community events that I haven’t brought myself to attend. I keep grumbling about the vibes in my local DSA chapter, but what do I know? I haven’t been to a meeting in ages. And yet, thanks to a couple good years of showing up more deliberately with those around me, I’m now welcomed into more opportunities to care and be cared for than at any other stage in my life. You all, in the lasts seventy two hours, neighbors have asked me to…

…help find a physical space for people to assemble zine and whistle kits/ pass out a bag of fifty of those kits myself/get plugged into a new mutual aid Signal group for our neighborhood/run a carpool for middle schoolers to and from a forensics tournaments/set up and take down a training for protest marshals/attend three different committee meetings/cheer, alongside my neighbors, for the five hundred person solidarity bike ride in honor of Alex Pretti/watch other people’s kids after school/learn how to play Wingspan at a community game night/show up at an alderperson’s forum on potential ICE activity in the area/(finally) get involved in a Slack group for a really inspiring gubernatorial campaign/lace up my skates at a “the river’s finally frozen enough for ice skating” bonfire party/gather with friends for a neighborhood spaghetti dinner/bowl (not alone!) with an even wider group of friends afterwards.

All tiny actions, mind you. Some of them available to me because I pushed myself to attend an event last week, or last month, or last year. Others that emerged from deeper conversations at school pick up, or brainstorming at a potluck, or because I showed up for friends frequently enough that they now trust me to keep doing so. But all of them, importantly, making it more likely that I keep doing things, with other people, rather than just clicking refresh on a fresh piece of outrage bait.

A quick aside, for the beloved introverts already rolling their eyes at me

I understand that all this sounds exhausting, my friends. And believe it or not, I too dread new social gatherings. Do you know what I earnestly love? A quiet evening in my own house. Having run community building trainings for years, I wish I had a magic word that could melt away social anxiety, or make small talk less annoying, or disappear the exhaustion of a fuller social calendar. I don’t. It does take a lot out of us, especially in those shaking early days of showing up for the first time.

What I will offer, though, is that there’s a reason why Priya Parker discovered, when she sought out the best gatherers across the nation, that a huge percentage of them identify as introverts. My friends, if you’re the kind of person who is better attuned, due to your introversion, to the missteps and omissions that frequently make social events unbearable, then you have a huge potential gift to offer the rest of us. You have a unique insight into how to craft an invitation and a space (even if it’s just for a couple people) that avoids those pitfalls. I don’t pretend that this is a fully satisfying aside, but it’s earnest. Gearing up to show up will sap your energy, at least at first, but I thank you in advance for giving it a try. And also, if you give it a go a couple times and it’s just one disaster after another, please reach out to me. I may not have a solution, but I can guarantee that I’ll have plenty of empathy.

REASON FOUR: It’s so much easier to ask people to do hard things together if you already love and trust each other.

One reason why I’m often confused by the “what should I do?” question is because, honestly, there’s so much to do right now. We are either now or soon will be called on to participate in boycotts, support strikes, pester existing public officials, elect significantly better public officials, protest in the streets, commit civil disobedience, make phone calls, deliver food, raise and distribute funds, and take care of each other while we do so. There are and will continue to be so many meetings. Oh my God, so many meetings.

It strikes me, then, that rather than asking others “what should I do?” we should ask ourselves “who can I invite to join me in any of these actions? Who in my life would attend a protest with me if I asked, or watch my kids so that I can attend a city council meeting, or would let me return the favor for them? Who would deliver me a lasagna for dinner if I was stressed and needed more time for organizing? Who would tell me to take a rest, when I had been running for a while and it was time to pass a baton?”

That’s why you host a game night. That’s why you throw potlucks. Because it’s through shared time together that you end up loving people, and it’s only through loving one another that we truly feel comfortable asking for and receiving help. You deserve a true network of support, and quite frankly, we need you to cultivate that network, because it’s only when you’re surrounded by love that you’ll keep showing up, not just tomorrow but a year from now, when we need you the most.

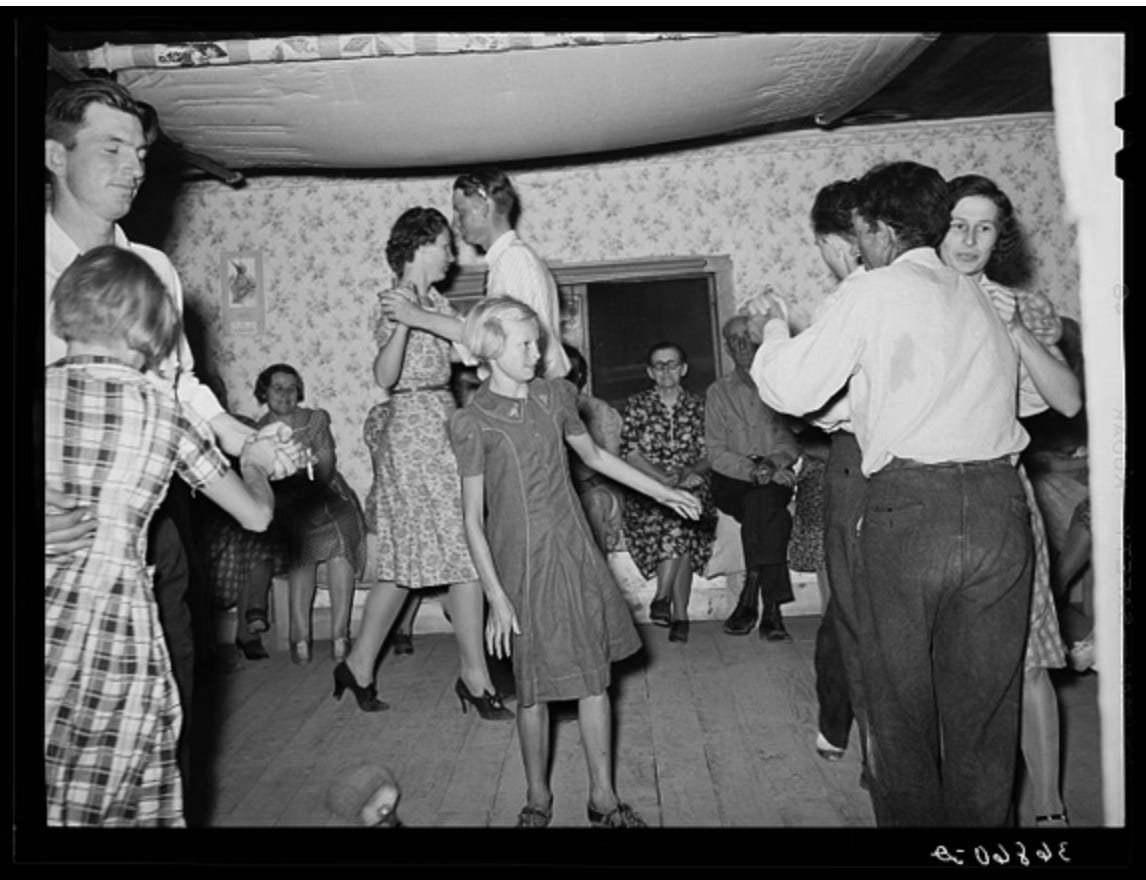

REASON FIVE: The most effective anti-fascists have always been the best community builders

Here’s a pretty trenchant quote.

“Community is a necessary aspect of human life, indeed of all creation, wherever life and growth is found. No tree, no flower, no blade of grass would be able to grow and to thrive alone on this earth, for they would be knocked over by the wind, pelted by the rain, or dried out by the blazing rays of the sun, if indeed they did not grow up together in common, mutually protecting and nourishing one another.”

I’m a bit jealous that I didn’t come up with that myself, and even more so that I’m a couple hundred years too late. That’s from Severin Jørgensen, one of the pioneering organizers of the Danish cooperative movement in the late nineteenth century. While frequently taken for granted, there’s a reason why the Nordic countries (previously some of the most unequal societies in Europe) were able to transform, in the twentieth century, into some of the most equitable and democratic in human history. It’s because, long before gaining power, they built dense networks of cooperative care infrastructure. What became the Social Democratic parties in Sweden, Norway and Denmark emerged first from a web of folk schools, labor unions and co-ops. The Swedes, Norwegians and Danes built community first, then took over municipal governments, then transformed their countries as a whole.

As they did so, Nordic activists had to weather attacks both from internal enemies (big business and aristocrats) and also literal Nazis. I bring this point up deliberately, because one of the other cynical rejoinders to community-focused activism is that you can’t counter fascism with co-ops and neighborhood associations. To the contrary, if you compare the Danish citizen response to Nazi occupation to that of other countries with less robust care networks, the difference is striking.

Not only was Danish resistance successful in keeping a significantly higher percentage of its country’s Jewish population safe, but neighborhood-based sabotage campaigns actively slowed down Nazi repression in meaningful ways, in spite of betrayal and cowardice on the part of Danish elites. The Danes, far more than many of their occupied counterparts, were a constant bee in the Third Reich’s bonnet. Not, it should be noted, because they hated fascism more than citizens of other countries, but because when the fascists rolled in, they didn’t have to build neighborly connections from scratch.

I know I can’t shut up about the Nordics in particular, but they aren’t the only activists who discovered that empires fall when community bonds are strongest.

Do you know what Indian organizers did before they marched to the sea and kicked out the British? They built and sustained sewing cooperatives. They jumpstarted local economies, while also building civic ties that would later power their mass protest movement. Before satyagraha, there was swadeshi. Before a charismatic leader, there were every day Indians making a choice to get to know their local seamstress.

Similarly, in South Africa, do you know what formed the backbone of the anti-apartheid movement? Labor unions, of course, but not just any labor unions. That country’s liberation movement had largely grown stagnant by the 1970s, when the unions serving Black South African workers shifted their organizing strategy from a top down model that merely asked workers to show up for mass protests to a more democratic one focused on empowering members to address their immediate shop floor grievances together. As Niall Reddy noted in his survey of that era in South African politics, “a movement reliant on charismatic leaders or outsider activists would be constantly vulnerable to decapitation by the authoritarian state. To survive, it had to be rooted in ordinary workers and capable of constantly re-generating new activists.”

REASON SIX: There’s nothing that oppressive regimes fear more than our love for each other

Hannah Arendt famously argued that the root of totalitarianism is loneliness. Apparently that’s a controversial statement amongst political scientists, though that strikes me as a pedantic debate. There is, in fact, plenty of evidence to support Arendt’s assertion, and more importantly, it’s a truism we all understand intuitively. When people are most alone, they’re more likely to be frightened, and therefore most susceptible to demagoguery. We get it. And oppressive states definitely get it. That’s why, historically, colonial powers have worked much harder to dismantle grassroots social movements focused on care rather than vanguard guerrilla cells. The former makes people feel stronger together, while the latter plays into the hands of whomever has the biggest guns.

Here in the U.S., J. Edgar Hoover was famously more frightened of the Black Panther Party’s visionary free breakfast program than their weaponry. In his own words, the Panthers sophisticated community care operations “represent[ed] the best and most influential activity going for the BPP and, as such, is potentially the greatest threat to efforts by authorities to neutralize the [Party] and destroy what it stands for.” When in doubt as to which of our tactics are most effective, always listen to the voices of our opponents.

When the question is merely one of force, the fascists always have the upper hand. What they don’t have, however, is a permanent monopoly on a populace’s opinion of each other. When the chorus of trust, love and solidarity grows louder than the regime’s attempts to spook and turn us against one another, we win. We literally drain fascism of its lifeblood.

REASON SEVEN: Opposition and outrage can only take us so far, but there’s no limit to how much we can build together

I know that, for many of us, it’s impossible to see to the other side of this era in American politics. But my friends, it’s crucial, for our collective survival, that we imagine a world in which we aren’t merely fighting Trump but actually shaping the society of our dreams.

Let us not forget. We defeated Trump once before. And speaking just for myself, that was the moment to keep building, the day after we celebrated in the streets. Some of you did so, and your communities are stronger for it. But too many of us didn’t. We breathed a sigh of relief and crossed our fingers that the worst was behind us. It wasn’t.

Rage gets us one step down the road. Heartbreak another. But we’ll burn out if that’s all that sustains us. If we want to keep moving forward, we have to feed each other. With our love. With our laughter. With shoulders to cry on. With stories that were once our own but have long since become shared lore. With casserole dishes filled to the brim. With care for all of our children, all of our elders, all of the loneliest friends in our midst. With memories, now distant, of the days when we didn’t know each other, and how much worse it felt. With relationships, once frayed, now repaired. With mistakes made, and grace both given and received. With a promise, first whispered tentatively, then shouted with full throat. The best is yet to come. There’s a beautiful destination ahead of us. We just can't get there alone.

End notes:

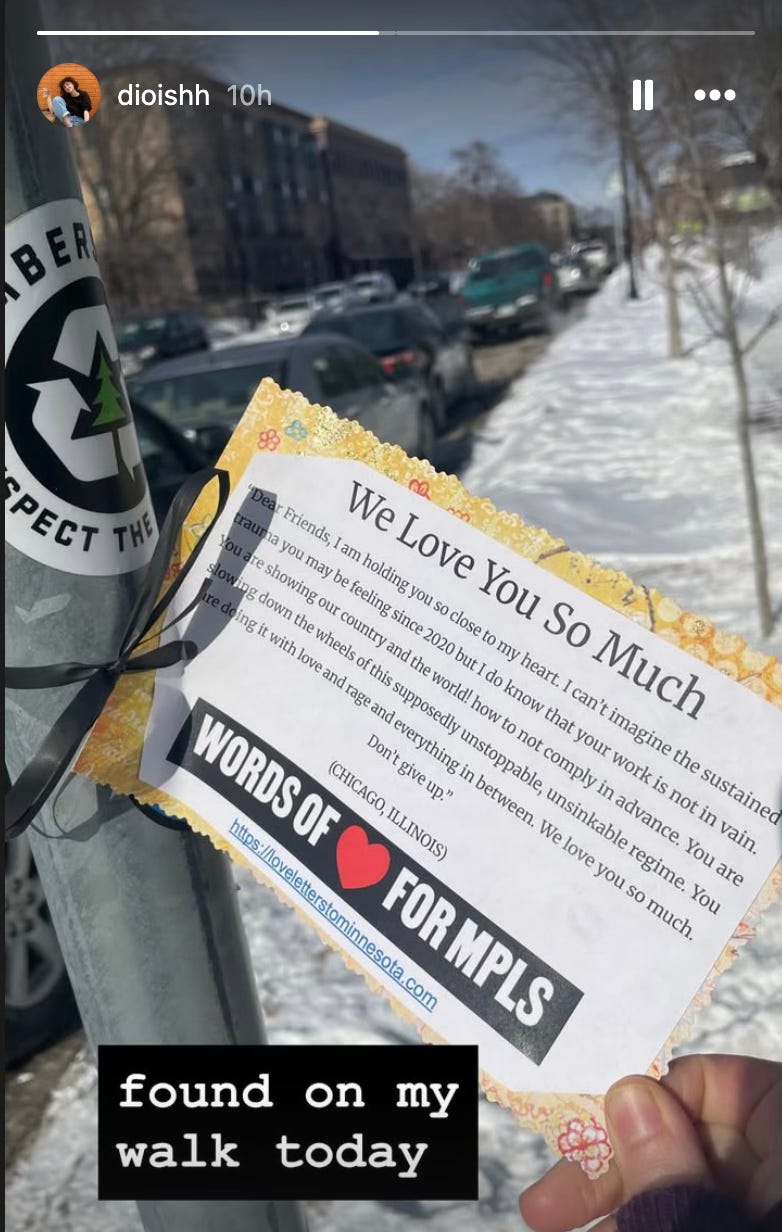

Two important repeats from last week’s essays: First, Minnesota needs an eviction moratorium, because a ton of neighbors there are too scared to go to work and therefore don’t have money for rent. Last week, folks sent me and Erin Boyle proof of more than $25,000 in donations. And we’re so appreciative, as are our friends in Minnesota. Let’s keep going. I’m immensely proud of our progress, but so many families are facing immense hardship right now. Keep. Chipping. IN!

Secondly, speaking of projects that have been fun to do, have you checked out loveletterstominnesota.com yet? Have you added yours in? It’s been so fun to hear about activists on the ground hanging them up around MPLS and then having their neighbors discover them.

New paid subscribers who’ve requested merch: I’ve been delayed, but I’m sending merch shipments out this week (including that lovely poster design).

Wait, you may be wondering, do I really give free merch (eventually, sometimes I’m slow) to paid subscribers? I do. I also keep a subscription cost down, and offer a whole bunch of other perks. Why? Because I’m grateful to get to do this work, and fully reliant on paid subscriptions to do so, and so how can I keep but thanking you, in so many ways? This is the time of year where new subscriptions go a long way in particular, so thank you!

I’m super excited to join one of my favorite writers, Celeste Davis of Matriarchal Blessing, for a Substack Live, tomorrow at 9:00 AM Pacific Time. Here’s the link!

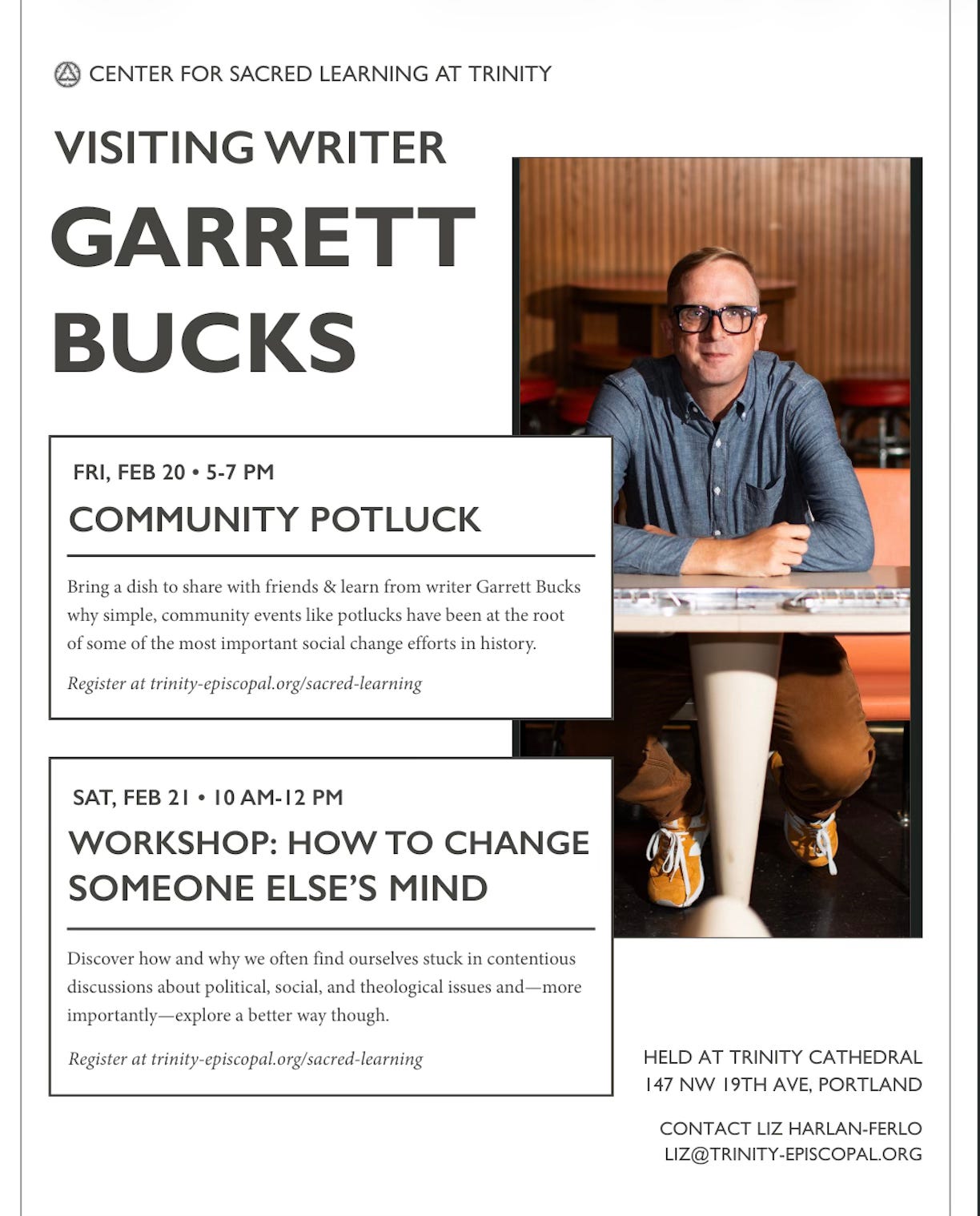

Oh, here’s a FUN announcement. PORTLAND, OREGON. I’m finally coming your way. And I’m offering two public events. Both at Trinity Episcopal (in the heart of downtown). Please come. Please invite friends, or organizing partners, or strangers you only sort of know. What a good excuse to practice putting the invitation out, right? Register for both at trinity-episcopal.org/sacred-learning

I apologize in advance, during a moment when I know there’s high demand for trainings, that I’m not currently offering any Barnraisers courses. I will soon, I promise. I’m working on a very exciting project that’s about to launch (and that may take me to some of your communities, actually). I’ll announce that soon, and then once we’re on the other side of that launch I’ll be able to catch my breath and figure out the course schedule moving forward. In the meantime, are you on the interest list? I hope so! And stay tuned!

I put up a note, but will insert this here for folks that won't see it. I am managing my social anxiety and introversion by inviting people I know and then inviting THEM to bring someone I (maybe? probably?) don't. This saves me from awkwardly offering invites to folks I don't know and gets the ball rolling. (Social inertia is my friend.)

Feel free to steal/tweak this if it's helpful.