Meet the new money, same as the old money

Our summer movie series continues with Crazy Rich Asians and a story about coming of age in a world where the cast (occasionally) changes but the narrative doesn't

Garrett’s note: If you only have time to read only one White Pages essay this month, oh buddy this would be a great choice. While I’m doing most of our decade-retrospective summer movie series in the form of special events for paid subscribers (the live chats have been FUN, you all), I wanted to share this guest essay with everybody. It comes from Maureen Tang, an Associate Professor at Drexel University, a long-time White Pages/Barnraisers community member, and all-around wonderful person. To be honest, getting this essay in my inbox reminded me of why I started a movie series in the first place: our relationship to films is always fascinating, but especially when we notice what stories they’re trying to tell us (about ourselves, about our world, about our dreams, etc) . But don’t take my word for it. Enjoy Maureen’s great work here (and see below for information on how you can participate in this series as well).

In Crazy Rich Asians, NYU professor Rachel Chu (Constance Wu) and her boyfriend Nick Young (Henry Golding) travel to Singapore to meet Nick’s obscenely rich family at a wedding. The family is snooty and rejects her, but eventually her pluck and charm win them over. That’s basically it. If you like romantic comedies, you'll probably like this movie. It has attractive, well-dressed people amid beautiful tropical gardens and beaches. Awkwafina plays the sassy friend and Ken Jeong plays her dad, a Ken Jeong character. I particularly enjoyed the street-food vendor scenes featuring noodles and dumplings.

In previous editions of The White Pages summer movie series, one of the key questions Garrett Bucks considered was “in what ways is this movie a story of Whiteness?” That may seem like a more obvious topic when the movie in questions is an old John Wayne western rather than a contemporary romantic comedy with the word “Asian” literally in the title, but let’s unpack that a bit. Why is Crazy Rich Asians a story of Whiteness?

Exhibit 1: the title. Eleanor Young (Michelle Yeoh), the matriarch of the family, would never refer to herself as "Asian" any more than Rachel Chu would refer to herself as "North American". Lumping ethnicities from an enormous diverse continent into a single "Asian" label only makes sense if you're fitting people into an established hierarchy between White and Black and need some intermediate levels so you can market to a US audience.

Exhibit 2: the all-consuming glorification of wealth. Just as Eleanor explains that she sacrificed her interests, career, and even family life to marry into wealth, Whiteness in this country has frequently meant trading in your cultural identity for economic privilege. Scandinavian and German immigrants who moved to the western states? They were not-Indians and accepted readily. Irish and Italian immigrants in America's urban centers were excluded from “the melting pot” and discriminated against until the Great Migration, after which they mostly became White.

This particular devil’s bargain of assimilation is well trod territory (particularly in this newsletter). What I want to write about is the cultural void that this deal creates, the insidious mythology that is happy to step in and fill that void, and most importantly, how it might be overcome.

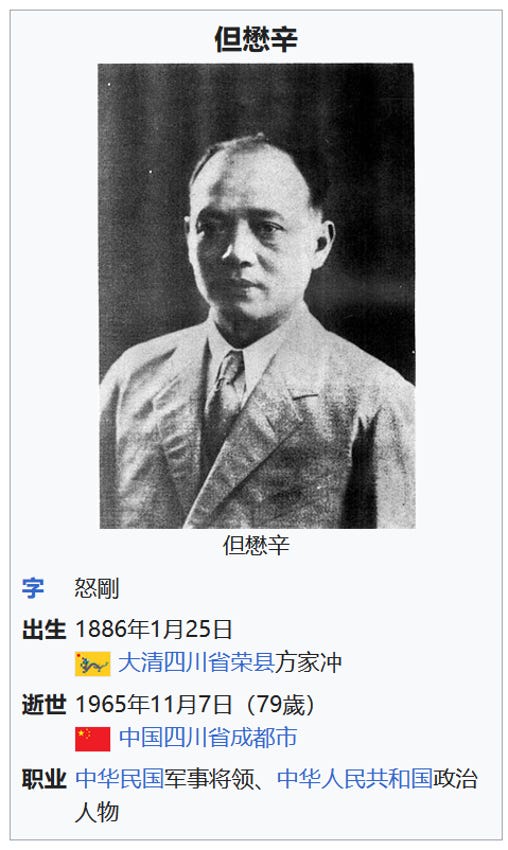

My grandfather's father was educated before there were universities in China. He studied in Japan, where he met Sun Yat-Sen and joined the Tongmenghui (Revolutionary Society). Back then, you didn't get to do things like that without money, and my great-grandfather had enough that in 1945, he sent his family out of China. My grandparents met on the boat. Both their families lost their physical fortunes in the Chinese Civil War and its aftermath, but intergenerational wealth takes many forms. My grandfather used his engineering degree and family connections to enroll in a program that funded advanced study for anti-Communist-affiliated Chinese. His doctorate at the University of Washington turned into a master’s after my father was born. My grandparents wanted my father to do well in school, so they spoke English at home. It worked; he grew up to pursue a PhD and successful career in industrial chemistry.My mother, also an engineer by training, came from a large Irish-American family. My parents met through the Delaware Valley chemical industry, got married, and started a bi-racial family before it was cool.

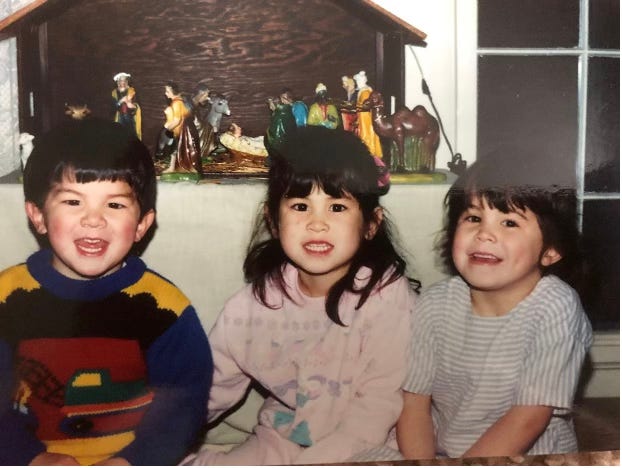

Hapa ha'oles were virtually unknown outside California and Hawaii in the 1980s and ‘90s, and as a result, I grew up thinking we were "the Chinese family". I checked the "Oriental" box on my standardized tests. Friends learned how to use chopsticks at our house. Strangers in the checkout line regularly asked my mother, "You have such beautiful children, where are they from?" One of them had grandchildren recently adopted from China, and she invited us to meet them at her pool since we had so much in common. My mom had nowhere better to take us, so we went! The house was back in the woods, one of those old-money Quaker estates, and the water was too cold to swim. The adopted children were infants.

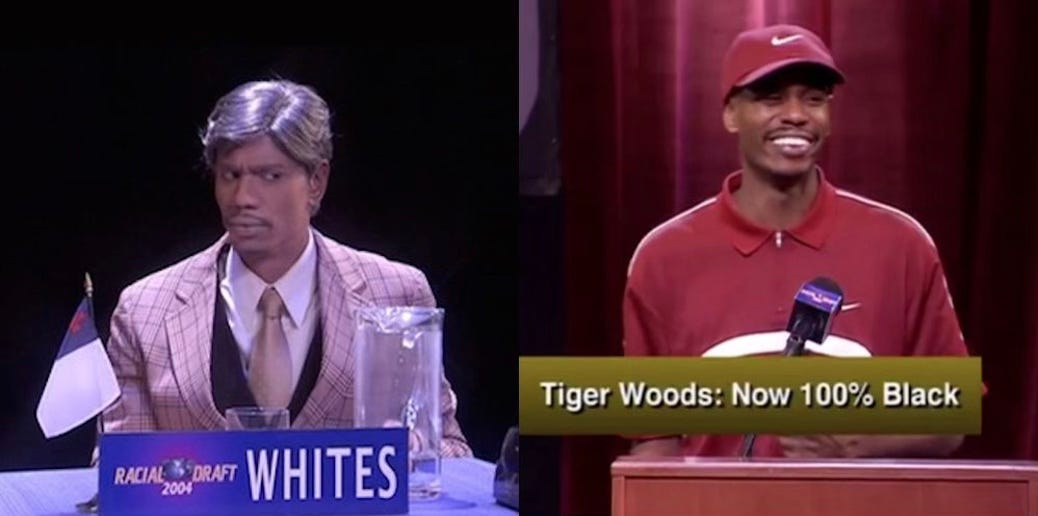

Fast forward to 2005, when my sister drunk-dialed me from the nation’s number one party school to ask 'did you know we are boring white girls from the suburbs?' Actually, I did know. I'd been through that discovery two years earlier when I learned at engineering school that a typical Chinese-American childhood extends beyond chopstick use to a) speaking Mandarin at home; b) going to Chinese School on Saturday mornings; c) eating food that is spicy and/or fermented; and d) if female, maintaining an adorable stationery collection in a Sanrio-branded pencil case. I knew nothing of these, so, in the parlance of the Chappelle Show, I drafted White.

As identity shocks go, Asian-to-White is almost certainly the best you can do for yourself, but it's still destabilizing to learn that the way you thought of yourself for 18 years is incorrect. It's even more challenging if "dissonance" and "identity" are not yet in the broader lexicon. What I now recognize as a subconscious yearning for cultural identity and heritage manifested two ways. First, I started voluntarily attending Mass with my roommate, just a few years after an enormous fight with my parents to not get confirmed. Second, I developed conservative political beliefs.

Today, my politics are about what you’d expect for a female Millennial professor who studied at Berkeley and reads this newsletter. But ::whispers:: my first voting was to re-elect W. And for years, I kept that a secret, not because I feared present-day repercussions but because I was ashamed of the ideas I supported and the decisions I made. Between my back-then political views and an abusive boyfriend who was integral to them, I had planned to leave that period of my life buried. Twenty years later, with Gen Z pulling hard to the right, excavating those memories feels worthwhile.

What I now remember most from politics in 2004 is that it felt good. The mythology of pioneers striking out into the wilderness and underdog colonists taking up arms for liberty was compelling. Believing in American exceptionalism and the wisdom of the Founding Fathers inspired confidence and pride. It was fun to root for the winning team. It felt smart to be a little bit contrarian, even countercultural, like a surprise twist that you'd never expect from me. What I can see from 2024 is that I desperately wanted a tradition and a heritage and a cultural identity to be proud of. And with this perspective, it’s obvious - that desire is nothing to be ashamed of. Of course I wanted that. I still do.

Let’s bring it back to the movie, and this year’s prompt. How does Crazy Rich Asians reflect our current moment and past decade?

Put simply, this movie is a bright, shiny example of the shallowness of contemporary DEI. I don’t want to imply that visible ethnic representation in Hollywood is a step backwards. It sounds like it meant a lot to the actors on set. But to me, sitting in the audience, putting Chinese faces on the same old trope-y rom-com plot is mostly a distraction from the ancient problems of fear and greed, and the modern problem of how capitalism has harnessed them for unprecedented destruction. Do you remember how exciting it was in 2020 when Aunt Jemima got canceled and all the brands suddenly added forward-looking web pages ? Do you remember how quickly they were revealed to be empty words? It turns out equitable and inclusive mission statements cannot mask a true mission to make as much money as humanly (or inhumanly) possible. Amazon and Target never cared about diversity; they cared about protecting their image to progressive consumers. Hollywood executives never cared about representation; they cared about tapping into growing markets.

Consistent with these priorities, Crazy Rich Asians lifts up ethnic diversity on a superficial level while uniformly accepting the materialistic values of status, money, and power. The nice cousin sits out of the catfight at the bachelorette shopping-spree. Why would she claw for designer clothes when she buys her jewelry from museum curators? Nick and the groom find the international-waters bachelor party distastefully excessive, so they helicopter away to a private island. Clearly, the real crime isn’t criminal wealth. It’s using that wealth to act common.

Let’s finish off by tying things together with the forward-looking, hopeful outlook that we’ve grown to expect from this publication. What does Crazy Rich Asians have to offer us who are dreaming so deeply of a better world?

It feels unfair to ask so much from a silly rom-com. Still, Rachel gives us a model for moving forward when our origin stories have been disrupted. In the climactic scene, Eleanor has outed Rachel’s sordid past: born in poverty, out of wedlock, the wrong kind of Chinese, completely unfit to marry into Singapore royalty. Rachel responds by defeating Eleanor in mahjongg with the help of her own mother, thereby embracing the aspects of her identity – working class childhood, raised by a single mom, professional game-theory expert - that are both authentic and worthy of pride.

Our own stories will have to find the same level of resonance. I can personally assure you that neither empty achievement nor a tortured sense of progressive superiority taste nearly as good as patriotic mythology. A lot of people, myself included, need to know where they come from, and that means stories with heroes. Convincing the Italian-Americans to abandon their statue of Christopher Columbus requires offering them a satisfying alternative. Finding that alternative in turn requires a deep dive into our individual and shared heritages and creating value from what we find.

For me, in 2025, the individual heritage is not ethnicity, but my father’s family tradition of intellectualism. Today’s unprecedented attacks on American higher education still pale next to the Cultural Revolution, but my great-grandfather survived and I can too. Meanwhile, my shared heritage is the ritual narrative of a faith tradition. Christianity has of course been responsible for horrible violence and abuse throughout history. Scripture and liturgy are also what I have inherited from my mother’s family, and they are my available framework for connecting to ancestors who experienced fear, grief, injustice, and uncertainty as we do today.

In the past decade, progressives have done so much to proliferate identity wheel worksheets but so little to coalesce around collective identity. Let’s do what we can to change that. “Heritage” is often coded for reactionary conservatism, but it doesn’t have to be that way. And so - which aspects of your heritage feel both authentic and worthy of pride? And which of those aspects can be shared?

End notes:

Song of the week (from Maureen): What's that? You're an elder Millennial reliving early adulthood with its search for identity and belonging and the thrill of discovering ideas bigger than yourself? And you're finding themes of regret and forgiveness and a complicated relationship with Christianity? And you’d like to soundtrack it all to accessible Bush-era indie? Have I got the SOTW for you! I've made a lot of mistakes but this pick isn't one of them.

One more note (also from Maureen): Irrelevant to the essay, but there are so many things wrong with this movie’s depiction of life in academia. An assistant professor at NYU would never be jetting off to Singapore for “spring break”. No way. She would be glued to her laptop, deep in the weeds of research papers. And no way is a first-gen-college-student-turned-R1-professor blindsided by her boyfriend’s intergenerational wealth. She has been climbing through elite institutions as an outsider for decades and become hyper-aware of class and educational privilege. She is possibly being eaten alive by imposter syndrome. No way. Rachel’s character only makes sense as an upper-middle-class suburbanite from Sunnyvale or Sugar Land.

And three final notes (from Garrett)

I know I said it already, but I just love this essay so much. Thanks for reading, friends, and thanks even more to Maureen for sharing with us.

Do you think you have an essay like this in you? We still have six more entries to go in our movie series. And while I can’t promise I’ll say yes to your pitch, I’m totally down to hear it, either on one of the movies currently in the queue or an alternate movie from any of our remaining years (2019-2024). As you probably picked up from Maureen’s entry, an ideal essay bridges the gap between personal essay and cultural/political commentary. I’m not interested in essays about why a movie is “good” or “bad.” What I’m craving is explorations about what the narratives either inside a film or surrounding it say about this absolutely wild decade we’ve all shared. I’mif you want to pitch (and I know I have to get back to a few of you- thanks for your patience).

One of my commitments to guest essayists: Great writing deserves to be compensated, and so (a). yes I will pay you and (b). I’ll make sure that I match or exceed the rates paid by the big outlets these days (your Times, The Atlantics, etc.). That feels very in tune with my values and the values of this space, but the dilemma is that I do not have the financial resources of The New York Times or The Atlantic. While I’m grateful for all of you who support this work financially, we’re still very much in the “holding this together with duct tape” stages of sustainability. If you appreciated this piece, would you consider pitching in to support The White Pages? Thank you.

The academia thing bothered me a little too! I definitely got my first exposure to wealthy Asian international students in grad school. I learned what Canada Goose and Moncler coats were (and here I thought my North Face puffy was fancy), so I’m sure Rachel would have seen that population at NYU and Stanford.

Maureen, thank you for sharing this! I come from Eastern European working class immigrants. On my dad's side, there is my grandfather, a stone mason by trade who used his chisels on the weekend to sculpt. His kids are almost all artists. On my mom's side are a bunch of resilient Polish ladies, who managed things like single-parenting while dad was in jail and wrote plays for their churches. We are a tough and creative folk, who have benefitted from the privilege that comes from easy assimilation into Whiteness.

And where do tough, creative, working class people find identity now? I found it in punk rock. :)