Long before the occupation, we were told a lie about Minneapolis

It's the same lie we've always been told about each other

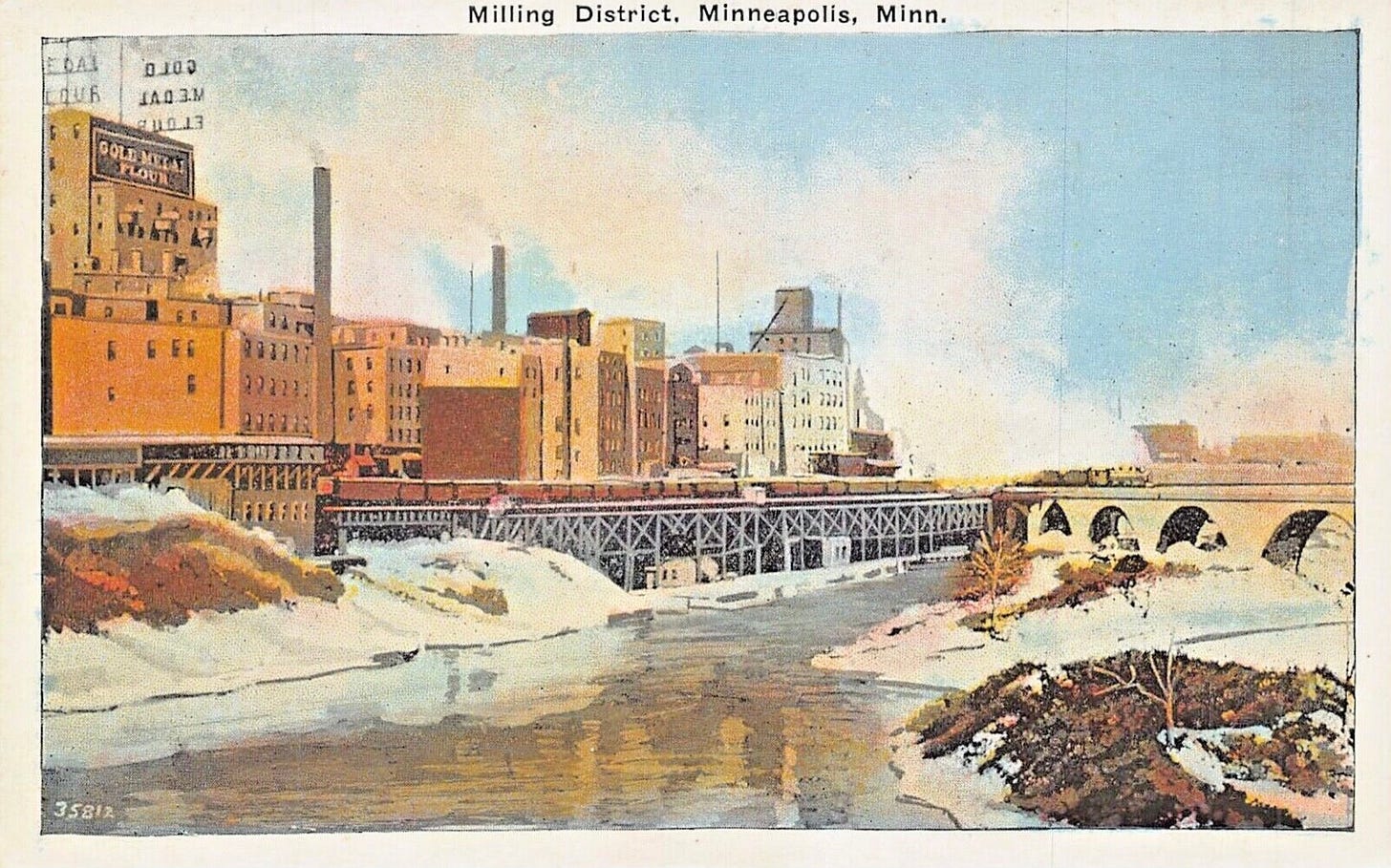

I can’t stop thinking about the railroad tracks that lead in and out of Minneapolis, about where they start and where they go. There was a time, not too long ago in the grand scheme of things, where nearly a quarter of wheat flour in the United States was milled in that town, in hulking factories lined up along the banks of the Mississippi. The mighty Saint Anthony Falls provided the power, an immigrant workforce provided the muscle, and Minneapolis fed the world. Not alone, though. You can’t mill wheat flour without wheat, which meant that, from its inception, the Mill City grew symbiotically with the prairies surrounding it. Across Rural Minnesota and the Dakotas, first came the farms, then came the depots and the grain elevators. Before long: orderly grids of streets. Churches. Schools. Bars. Diners. As in the city, so in the country.

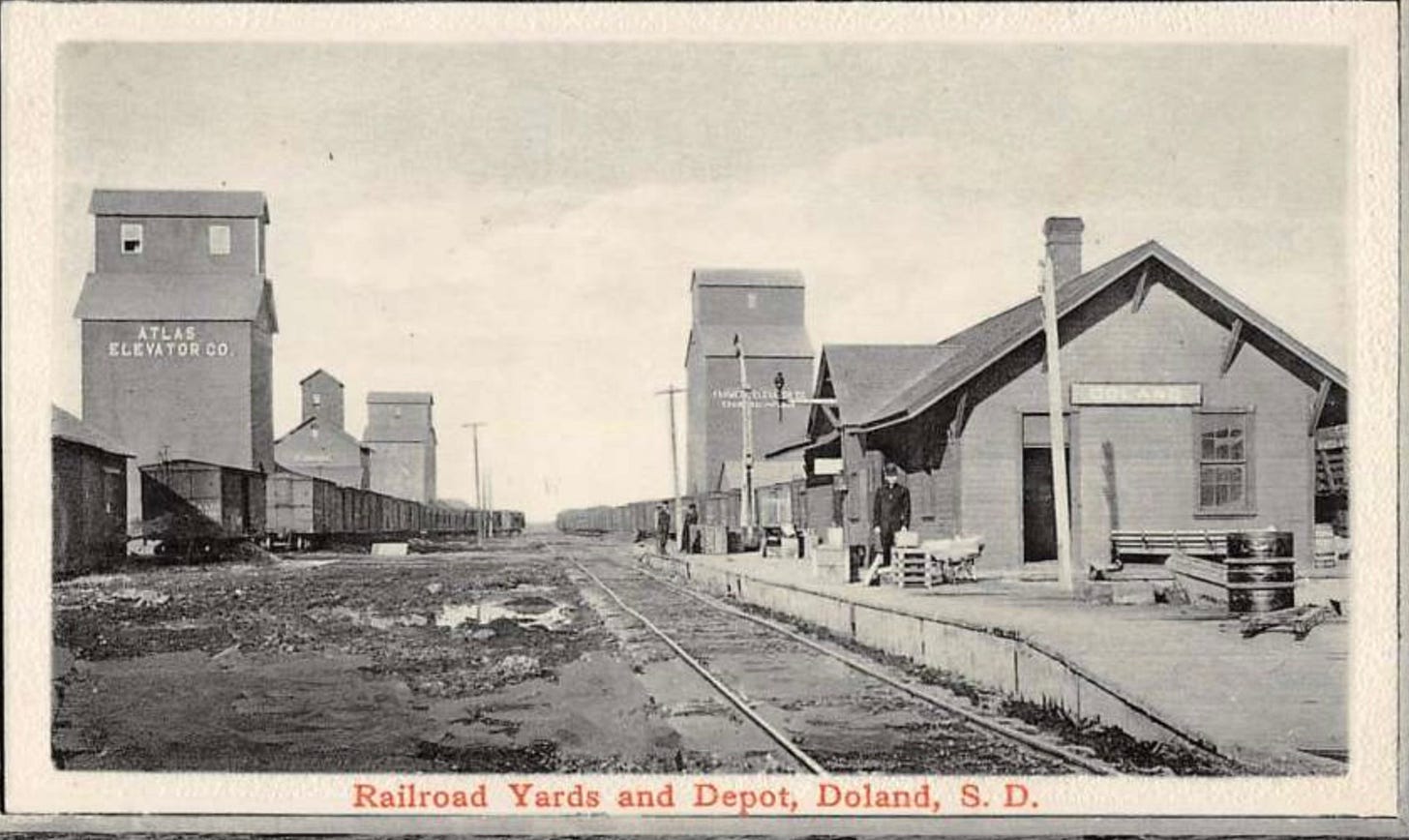

Founding a town on the prairie was a gambler’s enterprise. You’d make a guess as to where the Chicago and North Western railroad would lay tracks, and buy up plots of land along what you’d hope would be on the route. In 1882, a Civil War Veteran named Franklin Henry Doland guessed right, and so the town of Doland, South Dakota was born.

Six years later, on another patch of East River prairie about forty miles away from Doland, C.A. Bowley had the same good luck. He originally named his depot town Hazeldelle, a portmanteau of his chilrdens’ names, though it would eventually be shortened to Hazel.

Neither town ever grew into a metropolis, but they became homes. To farmers and school teachers and cafe owners and preachers and fuel truck drivers. They all did their jobs, as did their counterparts in the big city. Wheat made its way to the mills, and the towns and cities grew together.

I should pause here, before I fall into the trap of contrasting our fraught present and its jolts of defetishized violence with a gauzy, imagined past, one where chattel slavery and settler colonialism are minor footnotes rather than headlines. To be clear, before a place is “founded” by a random real estate speculator, it must be stolen and purged. Before any American origin story comes the original sin. Railroads were and are connectors, but often not benevolent ones.

So of course the farm towns and the city were never morally neutral spaces. But also, each subsequent generation who grows up with that legacy has a choice about whether we perpetuate, accentuate, or disrupt it. And so it matters that, for a time at least, it was possible to imagine that the city and the towns were not enemies, that they always relied on each other, that love for one was not negated by love for the other.

This, I’ve come to believe, is basically the American story. A core myth of disconnection and otherness, occasionally punctured by the truth that we’d be nothing without each other, that we’ll all perish if we remain more tightly bound to caste and exclusion than we are to one another’s hearts.

The most beloved mayor in Minneapolis history, Hubert Humphrey, didn’t grow up in the Mill City, but on the other end of those Chicago and Northwestern tracks, in Doland. He attended a Methodist Church that preached the Social Gospel, got a damned good education in Doland’s single schoolhouse, and learned about populist politics from his father, the town pharmacist. He was raised to believe that Doland was full of decent people who deserved a dignified life, but that all places were like that.

Humphrey came to Minneapolis, as is the case for so many other prairie kids, for school at the U. He took to his new home immediately, though there were detours along the way. For a time, he retreated back to South Dakota, as his family’s pharmacy business suffered both during and after the Great Depression. Later, he left for grad school in Louisiana, where witnessing Jim Crow up close ignited an anti-racial consciousness to match the class one already nurtured by his upbringing.

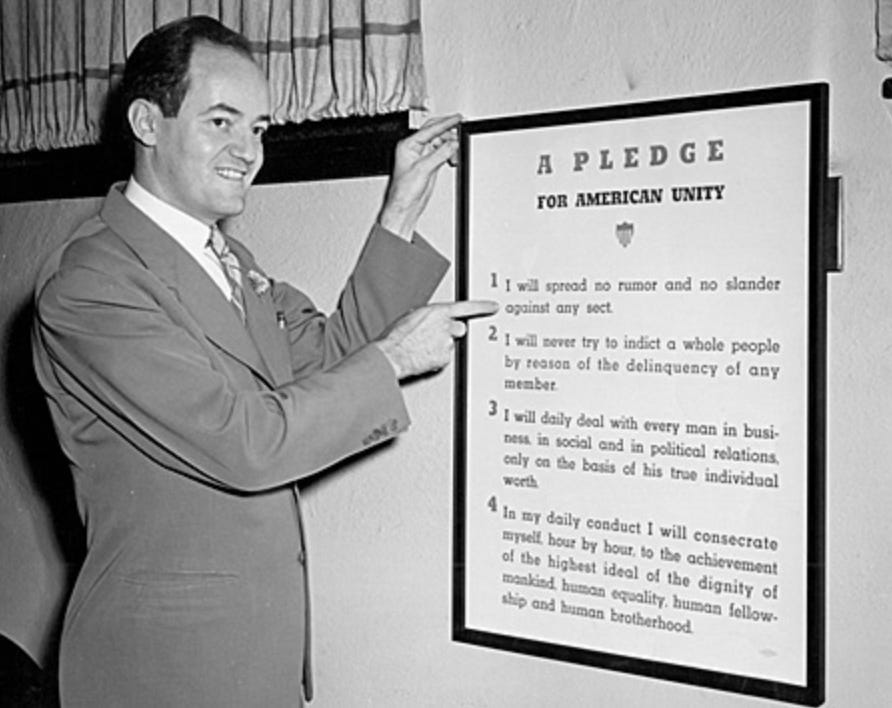

He loved his adopted hometown, but it wasn’t a blind love. Minneapolis in the 1940s was far from a utopia. Its downtown was controlled by gangsters, and its civic and political life was dominated by covert and overt racism and anti-semitism, including a 15,000 strong fascist paramilitary group with deep ties to the Republican Party. They called themselves the Silver Shirts, not even hiding their parallels to Hitler’s Brown Shirts.

Humphrey’s tenure as mayor is revered to this day, because he asked a city known for bias and hatred to believe it could be something different. He was a civil rights and anti-corruption mayor. He stood with Black and Jewish Minneapolitans, founded a model municipal Council on Human Relations and passed a Fair Employment act that made Minneapolis one of the few cities in the country at the time to ban racial discrimination in the workplace. He ran government fairly and decently, at a time, like now, when that was not a given.

From Minneapolis, Humphrey went to Washington. His star making move was standing up to the Dixiecrats who controlled the Democratic Party at the 1948 National Convention. He would end up being a key force behind some of the monumental progressive legislation in American history— the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Medicare, The Peace Corps and the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty. During those years he’d make frequent trips home, to both of the communities he still claimed. In high school gyms in Doland and Minneapolis alike, Humphrey would light up reconnecting with the farmers and factory workers whose names he still remembered. He had two home towns, the city and the prairie, always connected in his heart.

Humphrey was far from perfect, but I’ll save that broader career exegesis for another time. There’s no need to worship him as a hero. When he was at his best, Humphrey did something quite simple. He cared about all sorts of people because he cared for all sorts of places.

These past few weeks, Minneapolis has been under siege. Both by an idea, and by specific people. Donald Trump, Greg Bovino, Stephen Miller, and also Kristi Noem, Trump’s Secretary of Homeland Security and Hazel, South Dakota’s most famous daughter.

Noem is much younger than Humphrey. By the time she grew up, East River towns like Doland and Hazel had already been transformed by the broader demographic and political shifts that eventually built the MAGA geography we now take for granted. Family farmers who once fill the pews at social gospel churches or farmers’s union meetings couldn’t survive any more. Those that stayed did so as cogs in larger agribusiness machines. Towns died, and looked around for answers as to who killed them.

When it comes to a problem as vexing as rural America’s turn towards reactionary politics, there are no shortage of villains. It’s capitalism, of course, and the siren songs of white supremacy and patriarchy, those twin enablers of a world stuck in stasis. It’s the left’s institutional abandonment of places that used to be its core organizing home, and the right’s craven embrace of those places, less out of actual respect than opportunism. It’s bowling alone and empty union halls. It’s moral panics and exploitable biases. It’s tired old refrains, dusted off eery few years. “Don’t trust the cities: that’s where the Blacks are, or the immigrants, or the Queers, or the elites who love them more than they love people like you.”

What hasn’t changed is that towns like Doland and Hazel still produce ambitious young politicos. The difference is that Humphrey’s dad taught him about worker and farmer solidarity and Kristi Noem’s late father, who died when she was in her twenties and whose shadow looms large over her self mythology, mostly grumbled about the government and made her watch John Wayne movies. From this, it seems, she took three lessons: you only have to look out for yourself; if your family’s tourist ranch makes a lot of money, it’s solely because of your moral virtue and grit and not because of the thousands of dollars in government subsidies its received; and finally, if you put on the right outfit, you can convince anybody that you’re a cowboy.

Ask anybody who encountered Noem during her rise to power in South Dakota and you’ll hear the same refrain. She plays an ideologue on TV, but the only thing she truly believes in is her own career aspiration. That’s the classic devils’s bargain of the Trump administration. Who can say which is worse— the fascist true believers or the hollow vessels.

In practice, the silver shirts and the sycophants all sing the same song, one which we’ve heard played at the loudest possible volume: Real Americans, we are doing this in your name. The helicopters and the guns and the home invasions and the ripping human beings out of cars and the kidnapping children and the murders, don’t worry about it. In fact, celebrate it, because we’re doing it to your enemies. You have no kinship to those people in Minneapolis. Their humanity is not bound up in yours. There is nothing that might tie us together— the railroads or the rivers or the fact that our hearts beat loudest both when we’re scared and when we’re in love. They are fraudsters and gangsters and terrorists. They’d do the same to you, if they could. Believe us.

I am writing this at a tender, emergent moment. There are some signs that the occupation in Minnesota may be winding down, but nobody knows anything for sure. Perhaps I.C.E. will keep terrorizing that city. Perhaps it will come to my town next. Or yours. Perhaps this regime will take a lesson from previous administrations: do all the cruelty you want; just hide it better. Perhaps we have them on the run. They’re hiding Bovino from the cameras now. Will Noem be next? How many more deaths? How many more disappearances? We don’t know.

What we do know, however, is that to whatever extent any of us bought into the myth that we are not connected to one another, our neighbors in Minnesota, with their whistles and group chats, have revealed it to be a lie.

Like many of us, I’ve watched from afar, though I’ve done my best to be useful to activists I love and respect on the ground. Every day, more texts and calls. In their tears and shouts, I’ve heard every emotion under the sun: bone deep fatigue, terror, shock, trauma. And also: the greatest love ever felt, and a flavor of fearlessness that feels brand new. Not a naive fearlessness, mind you, one that assumes the worst can't come for any of us, but a fresh understanding that because we belong to each other, we will never walk into the breach alone.

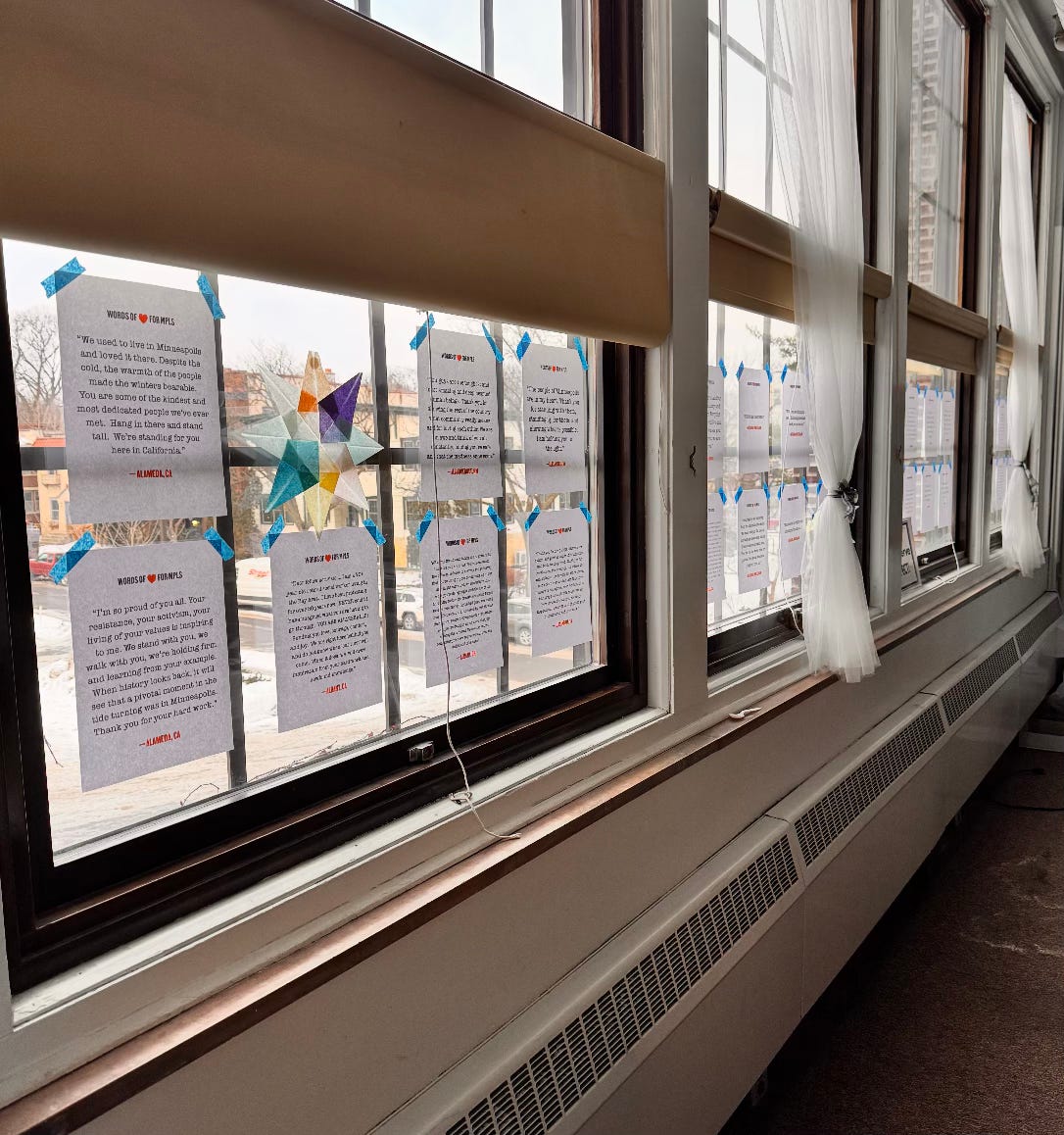

When I’m not trading messages with Minneapolis, I’ve spent the majority of the last few weeks immersed in tiny efforts that have put me in contact with so many hearts on fire across the world. A letter writing project. A fundraiser. And in doing so, I’ve noticed that it’s not only Minneapolis where neighbors are shaking off the myth that we aren’t bound to each other. There’s a reason why every time I put out a request, I receive hundreds of replies. We don’t pretend that our drops in the bucket make all the difference. It’s just that we long for one other. We long to break bread.

I asked people across the world to write love letters to Minneapolis and nearly a thousand have already done so. This morning, I woke up to a picture in my inbox. Dozens of those letters, hung up by a loving teacher in a bilingual Minneapolis elementary school. Look at us, belonging to each other.

People keep saying that there’s an awakening happening, and goodness I hope so, though that’s a cautious optimism. The entropy of everyday life— when the news cameras disappear and social media feeds return to “normal” — has a way of stifling radical awakenings. But still, when you hear louder and braver talk about how Minneapolis’ story is not only tragic but familiar— an echo of thousands of moments in our shared history history; of every occupation in history, from the colonization of the Americas to Gaza; of the ways in which policing has always operated on the Black side of town— that too is us belonging to one another.

I don’t know what comes next, you all. Or better put, I don’t know what the regime will throw at us. But I do know what we must do now. The story of Minneapolis this month has been of a web of neighbors holding tight. You don’t have to wait for an acute assault to build those webs where you live. The broader crisis of our unraveling from one another is enough.

In my town, people keep asking “what do we do to prepare if I.C.E. targets us like this?” I know that it’s unsatisfying to reply, “the same damn thing we should do if we aren’t next,” but that doesn’t make it any less true.

I can’t stop thinking about those railroad tracks. I can’t stop thinking about the river. I can’t stop thinking about our tears, or the laughter of our children, and how it sounds the same in every corner of this tattered country and ripped apart world. Webs of connection. They’ve been right in front of our faces the whole time.

The regime has one move. To tell some of us that the rest of us don’t matter. But that wheat had to be grown somewhere, milled somewhere, and baked somewhere. And if all those somewheres matter, then we can build a table that stretches between them all. If we all matter, then there’s plenty of bread to go around.

End notes:

I have a hunch that you’ll enjoy checking out loveletterstominnesota.com (and if you REALLY like it, check out the link to contribute your own).

Here’s the fundraiser that Erin Boyle and I are shouting about, in solidarity with activists in South Minneapolis. It’s for rent money, so that nobody gets thrown out on the street during an occupation. If you donate, do me a favor and email or DM me afterwards. We’re over $15,000 already, and well on the way to $20,000. We’d love to add your gift to the tally.

If you’re wondering whether I might spend more time thinking about tiny towns in South Dakota than most people (particularly the part about how those towns have changed, and what it means for all of us), then you’re right. Doland isn’t just Humphrey’s home. It’s also where my folks grew up and fell in love. I write about all that in my book (which is also about rediscovering politics as love and interconnection rather than just trying to win arguments), which you might like.

Speaking of books, Samuel Freedman’s masterwork about Humphrey’s tenure in Minneapolis, Into the Bright Sunshine is just the absolute best (and not just for weirdos like me who like reading about Midwestern politics from nearly a century ago).

Oh, and also: Yes, I’ll admit it. I’ve spent far too much time being perplexed by Kristi Noem, and more specifically how she came from the same part of South Dakota that I love so much and suffered the same core tragedy as my parents (losing their fathers in freak farm accidents), but chose such a dramatically different life path from my mom and dad. And yes, this fascination has resulted in me reading and writing essays about BOTH of her memoirs (and not just the parts about shooting dogs). Pretty good puns in both those essay titles, if I do say so myself.

Finally, please ignore this if you’re tapped out for “pass the hat” pleas right now because you’re prioritizing Minneapolis (keep doing that!), but if you (a). have a bit to spare and (b). you care about keeping The White Pages going, this work is a gift, but a perennially tenuous one. Last year at this time, I got a huge rush of new subscribers, which is incredible. And some of those new subscribers are in a position to keep supporting for another year, but others (understandably) aren’t. Could you pick up the baton? I keep the price pretty darn cheap (basically the lowest this platform will allow) and give you cool perks (like free merch) as a thank you. Thanks for considering.

Don’t have the cash for a subscription but want to help? Sharing essays you love with friends always goes a long way.

I want this printed in the NYTimes, the Atlantic, Politico, Fox fucking news. This is an outstanding essay.

Reading this on a train which feels right. And in happy tears at the picture of all those letters printed out. There are more of us.